Verscheen in International Symposium of Seoul Art Space GEUMCHEON op Oct 2011

An information society, Technology, Design, Art, Culture, and Industry

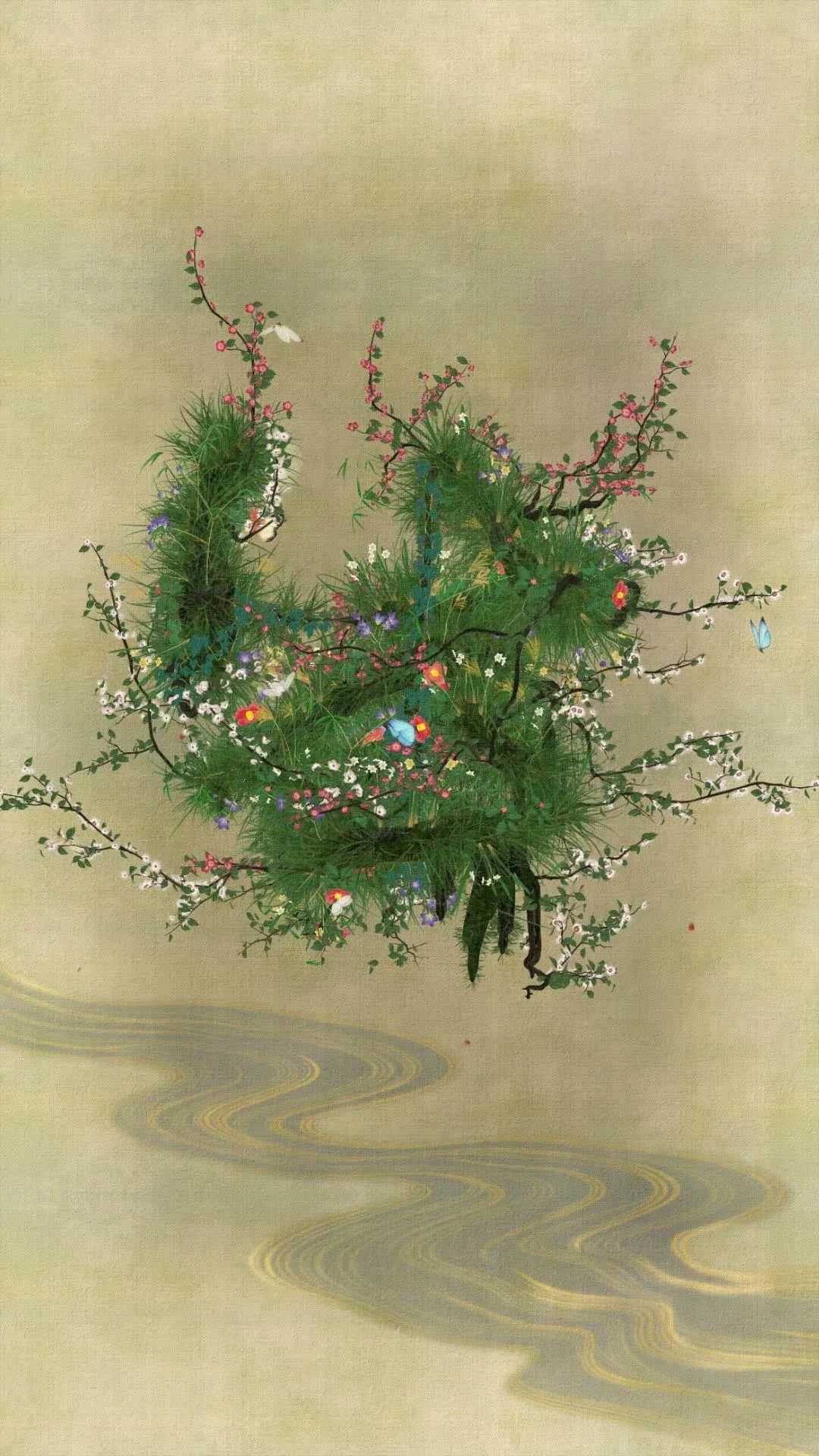

Before the information age, technology, design and art were clearly divided areas. However, the border has become blurred within the digital domain. For example, if we look at the interface of an I phone, it is difficult to define which parts are programming and which are the designer’s work. It turns out that both technology and design are concerned with the processing and relaying of information. Before digitalization it was necessary to have a physical substance for information to be transmitted through design or art. The situation changed with the digital age when information was released from the confines of having to be mediated through a physical substance, which in-turn necessitated the boundaries of design, art and technology. In the information society people tend to become expert in one particular field and therefore it has become harder to create art on an individual basis, this is why TEAMLAB utilizes the skills of a group of artists and technicians. [1] Competitive superiority = Region highly dependent on culture In informational society, another change has been taking place. The common speed which is verbalized domain becomes too fast. Therefore the region is no more the necessary condition in order to have an advantage in the competition. Before the information society, in case of iron-making technology, technological gap is caused by the country. But the technological gap has been reduced IT can logicalize and verbalize. However in domain where is highly depending on culture, can not explain verbally; for example, in domain such as “Cool, nice, interesting”. This methodology is difficult to share. We think that really is where the advantage of developed countries. The differences are much more in region where heavily dependent on culture. As a result, it leads to competitive force. In other word, we believe that the industry which rebuilds the region highly depended on culture with technology, and the developed countries with social infrastructure can get by in the world. In the informational society, a change has been taking place. The speed at which the verbalized world can be shared has increased so dramatically that competition for a particular geopgraphical area is no longer an advantage. Before the information society, in the case of iron-making technology, a technological gap was caused by the country. But the technological gap has been reduced by IT’s ability to logicalize and verbalize.[2]Japanese Culture and Japanese Spatial Recognition So what is Japanese culture? What is behind Japanese culture? How do we grasp culture? How do we take in, understand and see the world? At TEAMLAB we believe that we may be able to find answers to some of these questions through making art and through the creative process. Before the introduction of Western culture, the late Edo period (late 19th Century), Japan was a closed country to foreign commerce. During that time it is possible that people had a different way of seeing the world. Japanese painting lacked Western Perspective, and because of this it is often said that Japanese painting is flat. However, we propose that Japanese ancestors saw the world exactly as it is depicted in a classic Japanese print. When they looked at a Japanese painting they were able to see or feel the space in the painting, just as we see space and depth information in a modern day photograph. Considering this we at TEAMLAB began to wonder if Japanese didn’t have a different logic of space recognition to Western perspective.TEAMLAB video production TEAMLAB has made a number of video works that attempt to recreate the recognition of space of our Japanese ancestors’ in 3 dimensions. We hope that in the process we may be able to discover a new mode of expression. Example; the installation movie 100 YEARS SEA -Animation Diorama- [3] This work was created in a three dimensional computer space and the motion of the waves was computer generated. Then we converted the animation so that it could be visualized inline with our ideas concerning Japanese spatial recognition – the hypothesis that, Japanese painting was founded on a different logic of spatial awareness to that of perspective. Producing video works using Japanese spatial awareness has advantages over perspective [4]. For example, the middle of a movie theater is often considered the best place to view the movie, the visual experience becoming impaired with distance from the screen. However, using Japanese spatial awareness, there is no focal point and there is no need to identify with the location of the viewers. Therefore, the viewers can freely walk around the exhibition space. In addition it is not necessary to use a flat surface on which to project the image. In the case of the installation of “100 Years Sea”, the work was exhibited on screens that were at 90 degrees to each other without damaging the installation experience. Perhaps this can be understood in relation to the tradition of painting on Japanese folding screens. The work, ”Life survives by the power of life” [5] was exhibited as part of TEAMLAB’s “Live!” exhibition at Takashi Murakami’s Kaikai Kiki Gallery in Taipei in April of 2011, at the 54th “Future Pass” Venice Biennale, Hong Kong’s art fair “ART HK”, and “VOLTA” Basel, Switzerland. This work also uses the concept of Japanese spatial recognition. When shown as a still image the work appears flat, just as a Japanese print, but during playback it appears to occupy a 3 dimensional space.Japanese Subjective Space Description which supports “Narikiri” (Entering a Picture, or Visualizing a Picture from inside it) Western perspective is drawn from the view point of the artist and recognition of space can be thought of as fan-like. If you were to try to see the view as if you were in the picture, narikiri, then what you see would change. (In the case of a portrait painting the person in the picture would look back at the artist or viewer / figure A) However, the concept of the observing point in Yamato-e (Japanese painting) is weak, and the grasp of space is very different from that of perspective. If I draw a picture from the observation point of the person who is depicted in a Japanese painting, then the recognition of the space would almost be the same. [6] As mentioned above let’s assume that you are able to see the world as an ancient Japanese saw and recognized the world, as in Japanese paintings, and that you enter into a yamato-e picture. Unlike with a perspective painting the picture doesn’t change. Even though you become the character in the picture while viewing the picture, you can still keep watching it (Figure B). In the video game “Dragon Quest”, the players enter into the character whilst watching and playing the game. It gives them enjoyment because they enter into the world of the character and experience the picture the world of Dragon Quest as if they were in it. That is the spatial representation of “Dragon Quest (Figure C) [7]. However, as mentioned above, with Western perspective a person cannot enter the picture in the same way. Therefore the player of the game only sees details like the hand, handle, and cockpit of the airplane. Japanese spatial recognition supports the notion of “pretend” and its recognition is highly subjective. This subjective awareness goes together well with the information society.We believe that in the future when new industries emerge, if the industry and culture fit together well, then the strengths of the culture will be preserved for the benefit of the whole world. [1] We at TEAMLAB create teams of specialist among various fields who are able to transcend the boundaries of their own field of research. We attach importance to utilizing the discoveries that are made during the creative process for future projects.[2] We are Japanese and the topic is based on Japan, but it might share something in common with South East Asia.[3] 100 YEARS SEA -Animation Diorama- TEAMLAB, 2009, Animation Installation, 10min 00sec(19m 200mm × 2m 400mm) & 100 years(16:9 × 5) *2 versions, sound: Hideaki Takahashi[4] There are also disadvantages. Objective and physical size information is lost.[5] Life survives by the power of life[6] Some people would consider this idea ridiculous. However, perspective is also unnatural. The focus of the human eye is very narrow. The human eye does not clearly see detail like that of photographs and paintings of the Mona Lisa. The eye moves rapidly and the focus changes along the timeline. Information is synthesized along a narrow and shallow range of focus in the brain; the image just looks like a picture in perspective. That eye continuously takes thousands of photographs and synthesizes large numbers of pictures with a certain law in the brain to recognize the spatial perspective.[7] The method of expression of Japanese art fits well with game contents in which the main character is manipulated interactively. We believe that the Japanese game industry achieved much success due to utilizing the strengths of Japanese art representation.